A lot of mistakes and confusion in software development arise from conflating logical and physical concerns. For example, an object in a conceptual (logical) object model would usually be implemented by multiple objects in the implementation (physical) model. Not knowing this distinction might entice you to include all the implementation classes into the conceptual model, or not factor your implementation classes neatly. One layer down, this mistake is made again when mapping your objects to a data model.

This kind of mistake is so common, that I decided to try to write a little bit about it whenever I see this happening in practice. In this first post about it, I’ll talk about it in the context of Layered Architecture.

Layered architecture

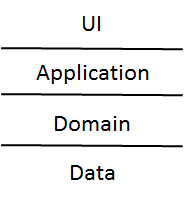

I don’t think the layered architecture style (or its cousin, hexagonal architecture) needs much of an introduction:

The UI layer is responsible for visualizing stuff, the application layer for managing the application state, the domain layer for enforcing business rules and the data layer manages the data. Every layer builds on top of the layers below it. It can know about those lower layers, but not about the layers above it. Depending on your point of view the data layer is sometimes thought of as an infrastructure layer which runs besides all the other layers. For the purpose of this discussion, that doesn’t matter much.

Logical vs Physical

So is the separation of layers a logical or a physical separation? This question raises another question: what it means to belong in a certain layer. Am I in the application layer because my code is in a namespace called MyAwesomeApp.AppLayer, or am I in the application layer because I behave according to its rules: I don’t know about the UI layer, and I don’t enforce business rules or do data management.

When it’s stated like that, you’re probably going to agree that it should be the latter. It doesn’t matter that much where you’re physically located, but only what you logically do. Yet, this is completely contrary to what I encounter in a lot of code bases.

A common sign is having your projects (or JARS, or packages, or namespaces, or whatever) named after their layers: MyAwesomeApp.UI, MyAwesomeApp.Application, MyAwesomeApp.Domain, MyAwesomeApp.DAL, etc. The UI package would contain your HTML, JavaScript and web endpoint code. The application layer would contain a couple of application services. The Domain layer would host our business rule code, presumably through a domain model. Finally, the DAL would do all the interactions with a given database.

So when is this a problem? Well, it doesn’t really have to be a problem, as long as you don’t need to do any, say, business logic in your UI or DAL package. But how often is this the case? In almost every project I work in there’s at least a bit of client-side (JavaScript) validation going on, which is definitely a business rule. Yet, this code lives in the UI layer. Or, I might have a unique username constraint in my database (which is part of the DAL), which is also a business rule. I’m pretty sure this happens in any project of practical size.

Now, this isn’t really a big problem in itself either. There’s the problem of the naming being off since there’s business logic in the UI and DAL package, which you would expect in the domain layer and this probably causes some confusion to new-comers. Secondly, we might ‘forget’ applying a layered design inside the individual layers since it looks like we’ve given up on this architecture for this feature anyway (since we’re not putting it in the appropriate package). That causes that part of the code to be less well-designed.

A real problem occurs, however, when we dogmatically try to put the business rules in the domain layer anyway, an idea often strengthened by the (dogmatic) need to keep things DRY. Ways I’ve seen this gone and done wrong are at least the following:

- Putting JavaScript code in our domain package, and somehow merging that to the rest of JS code at build time. The causes major infra-headaches.

- Enforcing unique constraints and the like in memory. This doesn’t perform.

- Refrain from using purely client-side validations, and always go through the backend via ajax. Users won’t like the latency.

- Doing a lot of pub/sub with very generic types to be able to talk to another layer you shouldn’t know about anyway. In this code base, I have no idea what’s going on at runtime anymore.

- Endless discussions among developers to agree on where a given piece of code should go. This is just a waste of time.

And these are probably just the tip of the iceberg.

We can prevent this problem by allowing our packages to not map 1-to-1 to the physical layers. In this case it’s an easy discussion where code should go. Now, we need to apply a little more discipline within this package to still apply a layered architecture, but at least it will be an honest story. Another method is to package based on the role a given set of code has: one package has to do with client facing concerns, another with database concerns and yet another with a domain model. You might think these correspond very closely to UI/APP/Domain/Data layer, and you’d be right, but the intention is different. The fact that one package handles database concerns also means it can be responsible for handle business rules that can most efficiently be implemented in a database.

This way, your physical package structure doesn’t have to reflect the logical layers of your layered architecture. It’s OK to have some business rules in your JavaScript or database, and they still belong to the domain layer when you do. However, make sure you still maintain the constraints of the layered architecture within that physical package as well.

Conclusion

This is just one example where conflating logical and physical concerns can cause big problems in your code base. By untangling both, we can feel less dirty about ourselves when we put a certain piece of code in the ‘wrong’ layer and at the same time build more effective software.